The Significance Of The Zomato IPO

- Published

- Reading Time

- 4 minutes

- Contents

I spoke to a seasoned public markets investor last weekend who asked “What’s the significance of the Zomato IPO?”. Here’s my take on why this IPO means different things to different folks.

Public market investors and internet companies

- Zomato gives retail and institutional investors in India access to high-growth internet-scale businesses.

- And while some (or shall we say most) internet companies are still making EBITDA losses at their current stage, the pace of their growth and the scale of their ambitions is what gets investors excited.

- Zomato shows that you don’t need to cross two oceans to reach the shores of the US and list on the NASDAQ to get the best tech multiples – you can do it right here on the Indian stock exchanges. Zomato’s IPO book was covered 38x and the anchor investor list reads like The Complete Peerage of the world’s best investors.

- India’s stock markets offer some of the best scarcity premiums for growth. Consumer businesses in India routinely trade at some of the highest Price-to-Earnings multiples in the world (Hindustan Unilever 67x, Nestle India 79x) for run-of-the mill revenue growth (Hindustan Unilever 12% revenue growth over FY21-24E, Nestle India 12% over 2020-23E). As recently as 2019, the press was celebrating the inclusion of Britannia into the Nifty. As much as I love MarieGold biscuits with my morning chai – one needs to remember that this is a cookie company at the end of the day!

- An Indian company valued at sub-$1B shouldn’t be listed on the NASDAQ, where it will be a micro-to-small-cap stock, with little analyst coverage and limited visibility in a very, very deep and sophisticated market.

- And any business should, to the extent possible, list in its home market to continue to create wealth for its local investors, who are more likely than not to be its own customers for evermore. As my Blume Ventures colleague Ashish Fafadia says, “an ecosystem that does not create its own wealth is basically a colony“.

- There are of course incredible benefits to an IPO, apart from liquidity to its investors. Being listed helps in attracting talent with stock awards and stock options, and enhanced credit facilities by banks for working capital and long term business growth. And let’s not forget that listed market-cap is a liquid hard-currency that can be used in a merger or acquisition to turbo-charge growth or expand into new products and services.

Venture Capitalists

A common challenge of running a VC firm in India has been the inability to demonstrate exits and return cash to investors. There are now three distinct streams of activity at the margin, all of which point to faster, larger exits than ever before.

- The first is IPO activity. Zomato is the real takeoff point for Venture Capital activity as it allows limited partners / LPs (i.e. investors) in VC funds to have a lot more comfort with India as an investment destination, with visibility of an exit within a reasonable timeframe. So when the next LP asks “Where are the exits? Where are the cash-on-cash returns?”, General Partners at a VC firm can point them to Zomato and the stream of companies in the IPO queue.

- The second big event earlier this year, was actually the all-cash acquisition of a majority stake in BigBasket by the Tatas, India’s first industrial house. What this illustrates is that large industrial business houses are finally looking at M&A in order to accelerate their internet-first strategy. Recent tech issues at large banks highlight why this is an imperative. I call this the “phantom-CTO” effect – the harsh reality that in Nifty-50 companies, the CTO is not a Chief Technology Officer, but really a Chief Purchasing Officer who lines up software services vendors to outsource tech.

- In a sense what the Tatas have done with the BigBasket transaction, and then their Curefit and 1Mg investments is to say that – one: we think this is a large market; two: we’re willing to pay up for this tech acquisition and not buy it at the cheapest possible price; and three: to concede that they’re not buying a business for just its hard assets – but instead are buying their next generation of leaders and talent (“Mukesh Bansal joins Tata Digital in an executive role as President”), speed to market, and the startup culture of experimentation, fast implementation and blitz-scaling.

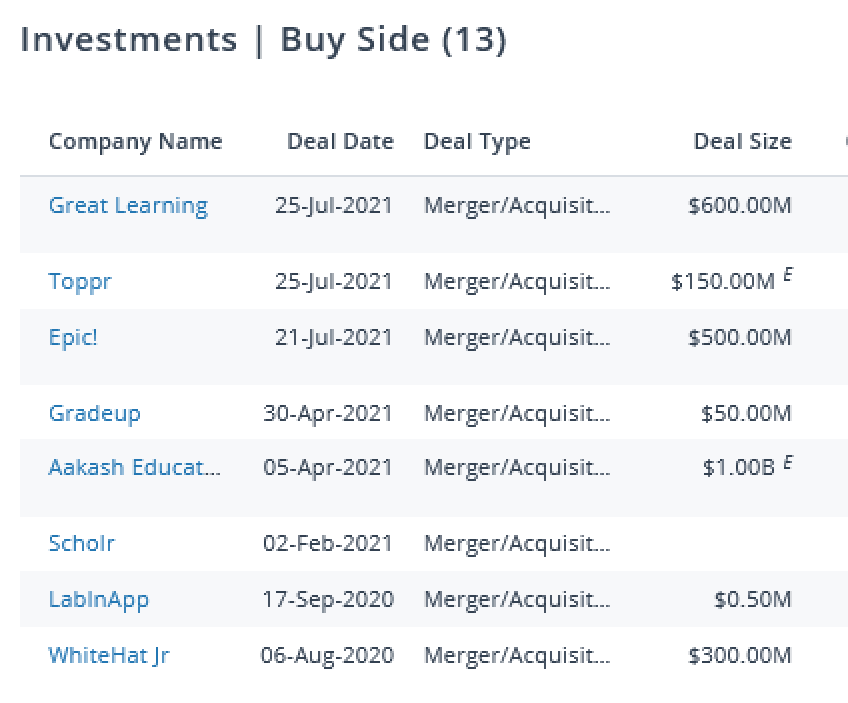

- Finally, the third series of events is the incessant acquisition juggernaut at large private companies. The ed-tech giants, Byju’s and Unacademy, have hoovered up 11 companies in the last year, with Buju’s alone spending $2.6B+ (largely cash) on its targets.

Buju’s has been on an acquisition juggernaut since the pandemic started (Data: Pitchbook)

- And there exist, at last count, over half-a-dozen VC-funded Thrasio-like startups in India with at least $250M in Seed funding to acquire fast-growing brands, revamp them, and grow them further. This hightened private M&A activity is what China internet was up to not too long ago – where early giants like Alibaba, Tencent and JD.com have used their superior access to capital to routinely swallow up challengers that round out their product offering, or to prevent these challengers from growing large enough to dethrone them.

Entrepreneurship

- By far, the most interesting and exciting aspect is that Zomato, and others that follow in its path, end up inspiring a whole generation of entrepreneurs with the right lessons.

- A corollary of Zomato’s success is that level-two and level-three leaders to the current core management team now have a nice nest egg on account of their IPO ESOPs, and decide to branch out to solve a new, interesting problem.

Every seminal tech IPO spawns the next generation of founders.

The Paypal mafia‘s second innings was to build another set of world-changing companies like Palantir, SpaceX, Tesla, LinkedIn, Affirm, YouTube and Yelp. The Flipkart mafia has followed that trailblazing path, founding Udaan, PhonePe, Groww, Cure.fit and Exotel.

I, for one, can’t wait to see what the #Zomans get up to next.